When thinking of high density, one of the most important issues is how we perceive it and how it affects us, the users of high density environments. The built environment affects directly personal relationships and neighborhood relations, while spatial configuration is an important factor in determining satisfaction of residents. Also, the experience of living in high density environments is much more complex than living in lower density environments. Thus, I believe that understanding the relationship between people and the built environment and the way in which high density affects human behavior and social relations is particularly important for designing and constructing new high-density residential environments.

Due to the urban way of life in which large populations of people live in artificially constructed areas, much of their behavior is thought to be influenced and guided by the architectural character of spaces and the qualities of the physical environment. The built physical environment manifests a direct influence on our behavior, on the social systems that govern our social group interactions and on our individual experience and behavior. People are in a permanent contact and exchange with their environment, and as Andrew Baum and Stuart Valins (1977) note in their book Architecture and Social Behavior, ”our behavior can be conceptualized as a dynamic sequence of adjustments and readjustments to our physical and social environment” (p. 1) [1]. The way in which the architectural configuration affects the behavior can be expressed as a function of ongoing or potential social dynamics and psychological orientations.

In the human interaction with the built environment and its influence on us, its effects are mediated by a number of variables with a high degree of complexity, which are involved within the framework in which the exchange between the individual and its environment takes place. In this framework, the effects of certain spatial configurations are manifested through complex interactions with other physical, social or psychological dynamics. Thereby, the effects of architecture are truly universal, overcoming aesthetic and symbolic properties, but they represent only a part of the overall effect that the environment has on us. Architecture influences our experience and behavior in the context of both general and specific variables. Thus inappropriate distance to certain objects, physical or social conditions of the built environment, spatial or functional distances between social groups can influence individuals, social behavior and the development of the group. Prior studies have shown that the variables of a configuration do influence the psychological and sociological processes, suggesting that some specific properties of the built environment affect social contact and its regulation, playing a key role in defining living conditions [1].

The implications of the high density environments on human behavior

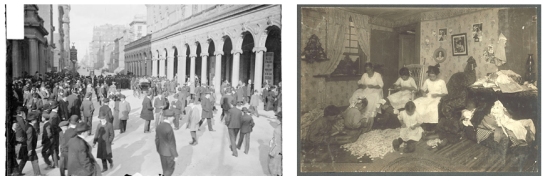

The scientific concern for the effects of crowding on people started to take shape with the beginnings of industrialization and becoming organized in the 1920s, coinciding with the moment in which for the first time urban population exceeded the rural population in American cities. The studies on its negative effects of urban life and implicitly of agglomeration on human behavior increased after the Second World War, when American and European cities recorded an unprecedented real estate boom. The first sociological studies on the influence of density are based on the premise that urban life is a continuous source of aggressive behavior, frustration and conflict that generates as a final result a number of evils and social dysfunctions.

Density and social pathologies

One of the first studies on the effects of crowding is Calhoun’s laboratory study, conducted on a population of rats. In laboratory conditions, populations of rats were subjected to spatial constraints and limitations, while being provided with enough water and food supplies. While the only limited resource was space, the rat population instead of growing exponentially because of food suffered a dramatic decrease, exhibiting violent and aggressive behavior, high infant mortality, a decreased quality of nests and even a lack of nest building exhibited by mothers, cannibalism, deviant sexual behavior, followed by asexual behavior and total withdrawal from the community’s social life.

The grouping of those manifestations was defined by Calhoun as a “behavioral sink”, and the conclusions of the study and the term that describes them became very influential after they were published, migrating from the academic area into urban culture. A behavioral sink is described as being “the outcome of any behavioral process that collects animals together in unusually great numbers. The unhealthy connotations of the term are not accidental: a behavioral sink does act to aggravate all forms of pathology that can be found within a group” (p. 144) [2]. Still, explaining a pathology relying exclusively on the conditions of high density has a limitation that was proven by further studies, and the extension of the study’s findings on the human urban population has been proven inconsistent. In fact, Calhoun’s study rather refers to different degrees of social interaction than simple physical conditions of density, demonstrating the alteration of normal social behaviors of animal populations through the stress caused by crowding conditions induces by a high density environment.

Crowding and behavior, a necessary distinction. The theory of density-intensity

The psychologist Jonathan Freedman (1975) conducted a lab research on people based on the performing of different tasks under different density and crowding conditions. He demonstrates that it is not density that determines the degenerative behavior of populations, but crowding. Crowding does support excessive social interaction and a lack of control over unwanted social contacts.

Freedman defines the framework for the study of high density consequences, noting the important distinction between crowding in physical terms, as defined by lack of space and the perceived crowding, defined as the “sensation of being crowded”, a distinct feeling from that of having very little space. The study of human behavior is related to the physical state of high density and not to the sensation, and the main issue in determining the effect of density is the control of other social factors (social variables) with which high density is generally associated, such as poverty, level of education, ethnicity. He elaborates the theory of density-intensity which supports the idea that crowding increases the importance of other people to the situation, as “[…] crowding by itself has neither good effects nor bad effects on people but rather serves to intensify the individual’s typical reactions to the situation” (p. 89-90) [3]. Crowding intensifies the importance of other people involved in the situation, the individual’s reaction towards the other participants as well as towards the situation itself. His findings support the fact that density doesn’t generally have negative effects on humans, but it intensifies the typical reactions towards other people involved in the crowding situation. Density itself is not unpleasant, but its perception depends on the situation, by the fact that the situation might be pleasant or unpleasant for the person experiencing it [3].

Architecture and behavior

One of the first sociological studies that relate the behavioral manifestations to the configuration of the built environment is that of Andrew Baum and Stuart Valins (1977) that compare the attitudes and behaviors of two similar groups of students that live in two different types of dormitories, with different planimetric layouts. The major difference between the dormitory layouts is a functional one, regarding the way in which the living units are grouped in relation to the common areas, while the amount of space provided per person is comparable. One of the dormitories has a corridor-design layout, in which the bedrooms are organized along one single hallway. The students who live in this configuration are exposed to a high level of interactions with a very large number of people. The other type of dormitory has a suite-design layout, with four or six person suits arranged along one central hallway. This configuration does sustain privacy and the possibility of filtering the unwanted interactions with other residents. The corridor-design dormitories, due to the spatial configuration of the layout, do not allow their residents to control the interactions with large numbers of students, also intensifying the consequences of interactions that can be perceived as stressful. The suite-design dormitories on the other hand offer their residents enough protection against unwanted social contacts, as well as control over desired contacts. The results of the study showed that students that lived in the corridor-design dormitories, being exposed to large groups and intense and uncontrollable social interactions have developed a greater sensitivity to group size and a lower tolerance towards crowding. Their way of adapting to the frequent and unregulated social interactions is generally withdrawal and avoidance of social interaction.

The conclusions show that the perception of crowding is a function of the frequency of interaction and unwanted and uncontrolled social contact, and it becomes negative in relation to both friends and strangers, at the moment in which the frequency of social contacts reaches a point where regulating interactions becomes difficult or even impossible. The negative feeling generated by crowding in relation to the architectural layout is translated by the two scientists as “a syndrome of stress related to the breakdown of social regulation” (p. 102), associated with loss of control and unsatisfying and unwanted interactions. Its most obvious manifestations are stress and avoidance behavior. However, the consequences of stress caused by crowding do not have long-term effects and its manifestations disappeared shortly after students have moved to other dormitory types available in the campus [1].

Social implications of high-density housing

Robert Edward Mitchell (1971) has studied the effects of high-density housing and housing units on the emotional health and family role relations in a very specific environment, that of Hong Kong. The habitation situations of Hong Kong provided many types of relationships between residents, housing units being shared by either members of the same family or by members of distinct families or households. Mitchell elaborates a set of considerations relevant for the influence of residential density on residents, establishing primarily that physical characteristics of density within the dwellings do not influence the level of emotional stress perceived by residents. The decisive influence on perceived stress is held by the social characteristics of the residential environment, especially the social composition of the dwelling unit, through the structure of social life and social control of the neighborhood. Thus, individuals do not respond directly to housing, since the effect of the architectural features of housing exerts an indirect influence. Instead, housing affects the patterns of social relations, and the individuals react to those social patterns that are influenced and determined by the architectural configuration.

The main effects due to housing with high density conditions identified by Mitchell are: clear awareness of lack of space in the housing unit, the influence of social structure on the internal relations of the housing unit, respectively the differences perceived in the situation of cohabitation of family members or people without family relationships, the latter condition leading to a state of increased stress. Stress amplifies in the case where avoiding unwanted contacts isn’t possible, mostly due to the home’s location in the higher levels of the building, where withdrawal to neutral spaces or public spaces is not possible. Other effects are parents having a decreased control of children through the fact that children are given a greater freedom in spending time outside the housing unit, and finally discouragement of social practices of friendship between neighbors and friends, since the usual entertaining practices aren’t carried out due to lack of space. Also, the study showed that individuals can bear high levels of density in the housing unit, provided only that members of a single family reside it [4].

The relation between apartments and the perception of the surroundings

A recent study from the area of environmental psychology is that of Annie Moch, Florence Bordas and Daniele Hermand (1996) that studies density subjectively perceived by the residents of collective housing estates from dense areas of Paris, respectively the 13th arrondissement. The researchers note that the need for privacy in the home is a basic need in relation to housing, with decisive influences on social life, while the lack of satisfying this need can have extremely negative influence on social life. Also, the feeling of congestion can be attributed to a number of different reasons, such as physical, social or individual factors.

Human perception of density in relation to the apartments is influenced by a number of variables, such as residential satisfaction, but also factors that are linked with the presence of other persons within the collective housing, such as interpersonal relations and the possibility to have control over social interactions. The residential satisfaction of the internal density of one’s apartment influences the perception of density of the surrounding neighborhood outside the apartment. The more residents perceive their own apartment as being cramped, respectively the available amount of space as insufficient, the more this subjective perception will extend outside, upon the whole neighborhood that will be perceived as overcrowded. Also, the perception of density depends on the social relations, because as crowding is stronger perceived, satisfaction towards social interactions with the neighbors is decreasing.

Density seems to be generally perceived by residents through the filter of other factors that people normally associate with the presence of others, such as high levels of noise, cleanliness, odors or unwanted interactions with others. Generally, the well-being of people is inversely proportional to the feeling of crowding, meaning that as density increases so does the feeling of annoyance towards the surrounding environment [5].

Social and psychological implications of high density city space

Bryan Lawson (2009) discusses the influences that the spatial arrangement of the public space and the elements from the immediate vicinity of housing have on the quality of life, calculated by the satisfaction measurement of the need for privacy, and on relationships within territory. He studies different situations of the public space, in relation with the generic perceptions that these generate.

Privacy and loneliness are considered to be subjective indicators of social interaction in public space, which do not have universal values since their perception depends on cultural variations, some cultures being more gregarious than others. Privacy refers to an individual’s ability to control the amount and type of contact he has with others and Lawson suggests that satisfying the need for privacy by design should be achieved by offering spatial boundaries that users can operate in order to organize hierarchically their social contacts, both inside and outside the home. On the other hand, Lawson comments on the general belief that high density entails an increased feeling of loneliness and a lowered sense of belonging to the neighborhood in terms of spatial design. He considers high density as having an altering effect on social trust that occurs when the public domain is not designed with consideration for hierarchy and local conditions.

On the perception of public space, an important role is played by the notions of private, public and semi-public space. Those notions are linked with the concept of territoriality, an attribute that refers to the social structure. The attachment towards certain territories, the clear awareness of borders and the tendency to defend them are manifestations of territoriality, and the modern city is a source of degradation of this feeling. The factors that are negatively influencing territoriality are: ambiguity of spatial design, uncertain borders and areas that are hard to defend. In relation to the environment, territoriality is identified with three needs: the need for stimulation, identity and security. The spatial configuration elements that can be traced by design in order to support the well-being of inhabitants are identified as: defining privacy by spatial borders that allow control over social contacts by the inhabitants of an apartment; offering relations for the apartment with public space that should contain also green areas with natural character, both visual and of access; maintaining areas with natural qualities in relation to urban spaces in areas of the city with high density, green qualitative and well maintained urban areas being considered to be the most important factor in determining the perceived quality of life in big cities; accessibility and quality of public transport; an increased level of security and a low level of anti-social behavior; noise control.

Through his study, Lawson proves that many of the problems generally attributed to high density are not in fact linked to numerical coefficients of distribution, but are more related to spatial geometry, although high density determines an increase of the negative perceptions of the environment. Thus, for a well balanced urban space in relation to the needs of its inhabitants, spatial configuration and the contents of that space are important, and problems of spatial perception could be avoided by an attentive design [6].

CONCLUSIONS

It is generally true that as population density increases, the greater the potential of emergence of conflicts and unpleasant situations. These negative manifestations of density are due to the increase of social contacts, and therefore of unwanted contacts, doubled by lack of control [1, 6]. They are not the result of physical density of people or spatial elements.

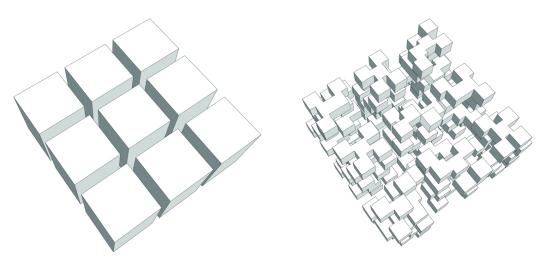

The determining factor influencing the perception of density by people who live in high-density environments is not density itself, as it’s tempting to easily deduct, but the combination of social and physical characteristics of space, decisive being the interaction between individual and the environment as a whole. Also, perceived density is influenced by a number of variables that are either individual cognitive attributes of the individual, or attributes of the environment in which he finds himself, so they may be physical, social, psychological and cultural [1, 6].

The built environment, both in terms of public space as well as building, if configured in a correct way can improve the perception of density, while if configured incorrectly may lead to a negative perception of density. A correctly built environment can, by means of its own configuration help to improve the perception of density and can alleviate negative feelings perceived by its residents generated by high density. Central to the relationship between architectural configuration, people’s experience and their behavior is the way in which built environment meets the needs and social expectations of its inhabitants.

References

[1] Baum A, Valins S. Architecture and Social Behavior: Psychological studies of social density. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1977.

[2] Calhoun JB. Population Density and Social Pathology. Scientific American, Vol. 206 (3), pp. 139–148, 1962.

[3] Freedman JL. Crowding and Behavior. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company, 1975.

[4] Mitchell RE. Some Social Implications of High Density Housing. American Sociological Review, Vol. 36, pp. 18-29, 1971.

[5] Moch A, Bordas F, Hermand D. Perceived density: how apartment dwellers view their surroundings. Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, 1996. URL: http://cybergeo.revues.org/294; accessed in 05.03.2012.

[6] Lawson B. The Social and Psychological Issues of High Density. In: Ng E, editor. Designing High-Density Cities for Social and Environmental Sustainability. London: Earthscan; pp. 285-292, 2010.

Excerpt from the paper:

Contemporary High-Density Housing. Social and Architectural Implications

written and presented at the QUESTIONS workshop held in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 14-16 july 2013; in process of printing at Acta Technica Napocensis: Civil Engineering & Architecture